Madrid is the great vacuum cleaner of migration between communities

Madrid has long become the great pole of attraction for migration from other autonomous communities. According to the National Institute of Statistics (INE), the preferred destination for internal migration was distributed among several areas in the last decades of the 20th century, but everything changed with the 2008 crisis. Since then, the Spanish prefer Madrid to emigrate: in In the 2020 pandemic, more than 70,000 people went there to live, compared to just over 40,000 in Barcelona.

The Casa de Andalucía in Barcelona has fewer and fewer members.

Also the Extremeño Center of Santurtzi, on the left bank of the Bilbao estuary. "We are 50% of those of the 80s," they detail.

At Gallego de Madrid, on the other hand, “we maintain our trajectory. Before there was only our Madrid city center and now there are I think a dozen. We have distributed ourselves, but due to the pull that the capital has we are renewing ourselves” explains Fernando Rey, its president.

Neither one nor the other is an exception.

Madrid acts as a vacuum cleaner for internal migration. First, as destiny. Because the capital is the one that attracts the most residents from other communities, even in years of pandemic, restrictions and confinements. 70,229 newcomers to the 2020 critic. In particular, it is a point of arrival for Andalusians, Extremadurans, Castilians, Galicians, Asturians and Cantabria. And when its bordering provinces are also influenced. Especially Toledo. Its 24,773 new residents speak for themselves. Barcelona, the second, remains at 43,561 new ones. The rest further.

In these territories, in addition, a large part of those displaced there arrive from localities considered to be from the same urban and border region, although these may be located within different provinces and communities.

Meanwhile, internal migration partially reverses the main origins and destinations of almost half a century ago. In Catalonia, those who change their residence to Andalusia (9,692), for example, are currently more than those who go from Andalusia to Catalan municipalities (7,870).

A dynamic that has deepened decade after decade since the 1970s.

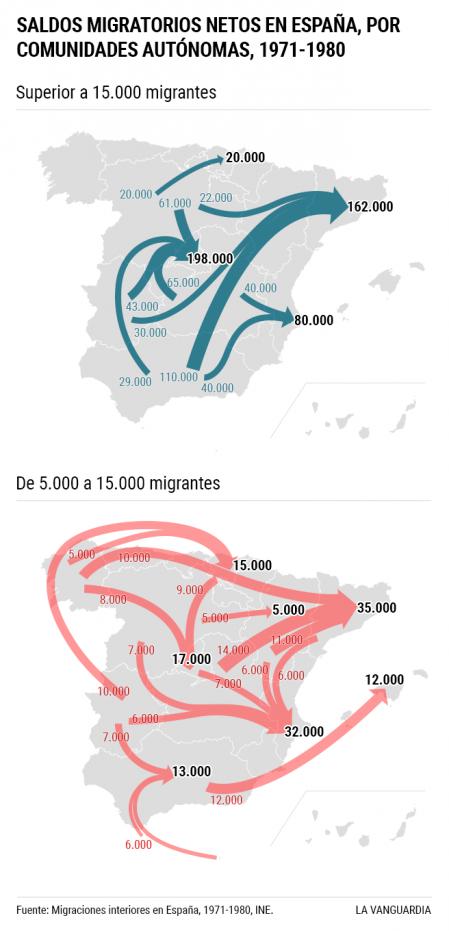

Because between 1970 and 1980 the main routes of migration in the interior of Spain were to Madrid, yes, but also to Catalonia, the Valencian Community and the Basque Country. Mostly from Andalusia, Extremadura, Galicia and the two Castillas.

"Until the 1970s and 1980s and since the mid-19th century, the migratory model in Spain was unbalanced and went to the central places for industry," says Javier Silvestre, professor of Economic History at the University of Zaragoza. "But then these destinations lose their attractiveness and new ones are added," he continues.

The history of change is well known. The oil shock of 1973 contributed to the collapse of the Spanish industrial model and the contested industrial reconversions of the following decade, for example on the left bank of Bilbao, were its consequence. It meant ending or greatly reducing its activity in the largest receiving destinations for immigrants.

The 'procés' is a consequence rather than a cause of the relative decline of Barcelona with respect to Madrid

Andrés Rodríguez-PoseLondon School of EconomicsThe deindustrialization, tertiarization and development of regional administrations are key. "The supply of labor was already showing signs of exhaustion after decades of massive rural exodus," adds Joaquín Recaño, professor and researcher of Human Geography at the Autonomous University of Barcelona. "The potential fishing grounds were heavily aged and masculinized."

The result of the change is reflected in the data for 2000 of the register, in which new destination players settle, such as the island communities, the Ebro valley and the Valencian Community thanks to mass tourism or its innovative industrial developments, according to experts. consulted.

However, twenty years later there is hardly any Madrid left.

"There has been a realignment towards Madrid as the main destination of internal migrations since the 2008 crisis, especially of non-residents." Andrés Artal, an economics professor at the Polytechnic University of Cartagena, who has studied this last period, argues this. And the reasons, he counters, are several.

They begin, he points out, in the boom prior to the crisis "due to the concentration of employment in the capital, which attracts more companies and relocates high- and low-skilled immigrants." Then, he continues, "it is important that construction, previously a relevant source of employment on the Mediterranean coast, sees a sharp drop with the bursting of the real estate bubble." And now, with the pandemic, tourism is joining.

Andrés Rodríguez-Pose, Professor of Economic Geography at the London School of Economics, goes further: “Barcelona, which was the best positioned city four decades ago to emerge as the main economic center, has lost out to Madrid”.

This academic argues it with the evolution of its population numbers, employment, human capital, foreign investment or regional wealth. But he highlights the institutional reasons: the rise of division in Barcelona along economic, social and identity lines would have led to a further breakdown of trust and the development of strong groups with a limited ability to connect with each other relative to Madrid.

“Multiple factors come together in destination selection decisions. And the institutional ones also count. The Basque conflict and ETA terrorism curtailed Bilbao's appeal for a long time”, he explains. “On the institutional issue in Barcelona –he continues–, it would suffice to say that the perception of Barcelona as a more polarized and exclusive city than Madrid (the famous 100 or 400, according to the interviewees, families that dominate Barcelona) has reduced its attractiveness as a destination for migrants, particularly the most qualified.

In this sense, the procés sees it as a consequence rather than a cause of this relative decline of Barcelona with respect to Madrid.

But, what is more, in the migrations between communities, Madrid again, always Madrid, is also today the protagonist as origin, although in a somewhat different dynamic from the most usual.

And it is that although the experts generally consider the great interregional migratory movements to be finished in the 1980s and if for that reason since then short-distance and residential migrations stand out as the most common, today another stands out: to Castilla- La Mancha and originating in Madrid is the main destination to which residence was changed in the latest INE report.

As Artal argues, the movements are replicated in the different urban areas and go from the center of the cities to their suburbs looking for areas with a better quality of life and lower prices due to the improvement in the connectivity of transport and communications. Everything, specifically, in "an endogenous growth model that is driven by urban agglomeration economies."

The concentration of employment in Madrid relocates high- and low-skilled immigrants

Andrés ArtalPolytechnic University of CartagenaAnd with him is that the extension of the capital is lengthened. Madrid increasingly includes other autonomous communities in the consolidation of its metropolitan region. Castilla-La Mancha stands out as its first outskirts. Something similar happens, although to a lesser extent, with Castilla y León. It is the Great Madrid.

It is with all these data in hand that for the experts Madrid distances itself from the other territories, also for internal migrations in Spain. It is symbolized by the profile of the people of Madrid, almost half of whom were born abroad. Very particularly in the two Castillas, in Andalusia and in Extremadura.

It is no coincidence like this, it is pointed out, that in recent months there have been several regional presidents who have demanded compensatory funds for the capital effect. Also the decentralization of certain institutions that can be located throughout Spain and attract socioeconomic activity as they do in Madrid.

Participate in the Discussion

4192